Polygon Miden: Asset Model

Polygon Miden continues to make progress toward a public testnet, expected in Q4 of this year. This blog post is the latest in a series covering Miden’s novel architecture, designed to enable developers to build high-throughput, privacy-enhanced applications.

Polygon Miden’s feature set requires a new way of thinking about assets and a new approach to storing them. In order to provide concurrency and privacy, assets need to be treated natively. Basically, the way Ethereum treats Ether, its native currency, is the approach Polygon Miden takes for all assets.

This post will cover the design of Polygon Miden’s asset model, how it compares to Ethereum’s, and how it allows for new features when implemented on an execution layer. The core goal of Polygon Miden is to extend the feature set of the EVM to create a forward-looking scaling solution that still inherits Ethereum’s security.

Assets on Ethereum

Ether is the native asset of Ethereum. And in a certain sense, it is the only native asset of Ethereum. Transaction fees are only paid in Ether. And every account on Ethereum has an Ether balance, meaning Ether is stored directly in Ethereum accounts. From a technical perspective, Ether is the only asset defined at the EVM level.

But there exist many other assets on Ethereum, from USDC to Bored Apes. Due to Ethereum’s permissionless nature and ability to execute arbitrary smart contracts, anyone can create assets on Ethereum. Those assets, however, are stored in smart contracts, not the owner’s accounts.

For example, an ERC20 token is represented by a contract. This contract is a simple registry that lists all the owners and their amounts in a global hashmap. The hashmap, in turn, tracks ownership. Transferring an ERC20 token, therefore, means changing the list of owners in that particular contract.

This model has tradeoffs. Transactions can only happen sequentially—there cannot be two different changes to that public list at the same time. And the list is public: Anyone can read the `balance_of` any other user.

Even the owner of an ERC20 token needs to look her balance up in those lists. This is why MetaMask doesn’t show all the tokens one possesses right away, but a user needs to add a token to get the balance. While ERC20 tokens are fungible, the model doesn’t change for non-fungible assets like NFTs using ERC-721.

Assets on Polygon Miden

On Polygon Miden, users can create and trade arbitrary fungible and non-fungible assets. The goal is that all assets on Polygon Miden are treated natively in the same way Ethereum treats Ether. The asset model describes how to issue, encode, and store assets. Native assets are data structures that follow the Polygon Miden asset model. However, there can also be alternative data structures of value that do not follow the asset model.

Faucets: Asset issuance

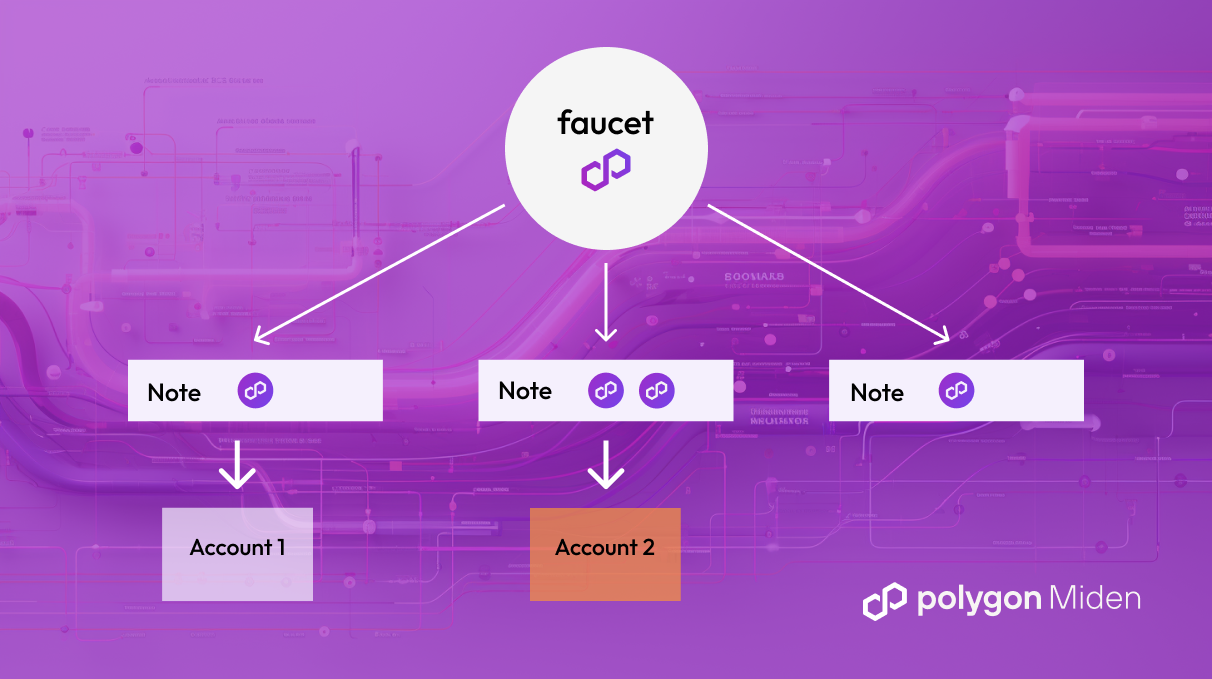

On Polygon Miden, specialized accounts—called faucets—can issue assets. However, anyone can create these accounts. Faucets can either issue fungible or non-fungible assets. The customizable code in those accounts defines the asset's properties, e.g., who can issue and when and what the maximum supply is. This way, it works similarly to the Ethereum ERC20 model.

The difference is that faucets do not track ownership. Instead, they produce notes in executing transactions to distribute the assets. As described in Polygon Miden’s transaction model, those notes carry the newly created assets to be consumed by other accounts. That way, one can mint a million NFTs locally in a single transaction and then send them out, as needed, in separate transactions in the future. If executed privately, the network would lose track of asset ownership from then on; one cannot query the asset account to get a balance.

Asset encoding

Assets need to follow a certain format so that every participant can easily identify them as such. Asset encoding defines the standardized form used to preserve information about the asset and to transmit or store it.

On Polygon Miden, all native assets are encoded using 256 bits. The asset encodes both the ID of the faucet and the respective asset details. Having the issuer's ID encoded in the asset makes it cost-efficient to determine the type of an asset inside and outside the Miden VM. And, representing the asset in a ‘Word’ means the representation is always a commitment to the asset data itself. This is particularly interesting for non-fungible assets, where the asset encoding expresses the asset itself.

Asset storage

On Polygon Miden, all assets are stored in the owner’s account itself or in a note. Accounts and notes have vaults to store them. Accounts may store an unlimited number of assets in a tiered sparse Merkle tree. Notes store assets in vectors of length 255.

Storing assets directly in accounts provides several benefits, including parallelizable transactions, off-chain storage, and programmable transaction fees.

Transactions on Polygon Miden always only touch a single account. So, if an account produces a note that carries an asset, only this account's vault needs to be updated, and the account hash will change. But there is no global list that needs to be updated with every transaction—no matter which asset is being transferred. This means that two accounts can produce notes carrying the same asset in parallel.

If an account is stored off-chain, then only its hash is known to the network; those accounts are considered private. That means no one knows which or how many assets one has, and no one can look it up. Hiding account balances from competitors and hackers could make web3 safer.

By treating all assets as native, users can pay fees using any asset on Polygon Miden. At least, there is nothing in the design that prevents this, though it’s dependent on the Polygon Miden Operator to accept fees in any asset.

Non-native assets

Polygon Miden can be used to create other types of assets as well. Developers can replicate the bespoke ERC20 model, where ownership is recorded in a single account. To transact, users would need to send a note to that account to change the global hashmap.

Furthermore, because accounts are transferable, a whole account can be treated as a programmable asset. For example, an account can be a “crypto kitty” with certain attributes and rules, and people can trade these “crypto kitties” by transferring accounts between each other.

Instead of a crypto kitty, we can also think of an account representing a car. While such an application is forward-looking, the owner of this car can change so the car account can be treated as an asset. In this car account, there could be all the rules defining how to update the car or who is allowed to drive and when.

The case for minimizing state growth

Polygon Miden’s method of storing assets also limits state growth. On a blockchain, state describes who owns what and the condition of all smart contracts at a certain point in time. This is true for Polygon Miden as it is with other rollups and smart contract blockchains. The state of a blockchain grows bigger the more it is used. This problem is known as state bloat.

Because the state of a network grows with every additional owner, the ERC20 model of using global hashmaps can lead to state bloat. Tracking ownership of all assets on-chain means no one can be deleted. On Polygon Miden, because assets can be stored in the account and accounts can be stored locally and privately, state doesn’t grow with every additional owner.

In these ways, the asset model for Polygon Miden is consistent with the rollup’s broader design goals of providing a secure environment for high-throughput and private applications.

For the latest, tune in to the Polygon Discord. And if you’re interested in (or perplexed by) Zero Knowledge and Polygon Miden, check out the docs.

Together, we can build an equitable future for all through the mass adoption of Web3!

Website | Twitter | Developer Twitter | Forum | Telegram | Reddit | Discord | Instagram | Facebook | LinkedIn

.png)

.png)